A group of distinguished journalists and academics, including two former regional press editors, have come together to take a look at how the phenomenon of social media has impacted on journalism, politics and wider society.

A group of distinguished journalists and academics, including two former regional press editors, have come together to take a look at how the phenomenon of social media has impacted on journalism, politics and wider society.

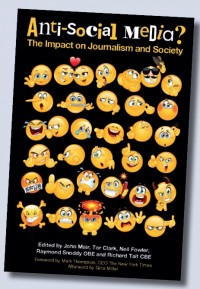

John Mair, Tor Clark, Neil Fowler, Raymond Snoddy and Richard Tait have co-edited a new book called ‘Anti-Social Media?’ which will be launched this afternoon at London’s Frontline Club.

We are serialising three chapters from the book on HoldtheFrontPage this week, beginning on Wednesday with Alan Geere’s look at modern-day newsrooms and continuing yesterday with Jim Chisholm on the impact of the so-called ‘Big Five’ digital players.

In our final extract today, journalism professor Chris Frost considers whether social media and the internet have changed journalists’ ethical practices.

Changes in the way journalists work over the past 20 years have caused many to ask whether publishing on the internet or social media should change the way journalists approach their craft both practically and ethically. The simple answer is that while the practice may have changed considerably, the underlying ethos of journalism and the ethics of its practice have remained fundamentally unchanged.

Of course that does not mean there are not new ethical problems and challenges; more ethical tripwires of which the good journalist needs to be aware and avoid. However the basic ethical underpinnings of journalism as outlined by codes around the world have not changed. Accuracy and truth remain at the heart of good journalism whilst concern for privacy, minors, the vulnerable and a policy of non-harassment, non-intrusion, non-discrimination and using straightforward means to gather stories unless there is a strong public interest continue to underpin the ethical demand to do no harm that is central to many journalism codes.

Internet publishing and researching is now too old and deeply embedded in journalism practice to be called new technology and did not in any case throw up, of itself, too many new ethical problems. The ability to use the technology to hack into people’s private affairs has been illegal since the serious introduction of desktop computers, not that that has always prevented unethical hacking of computers and phones as LJ Leveson heard at his 2011 inquiry.

It is the introduction of the smart phone and its access to the internet and the social media which sprung up in various forms over the past ten years which really allows journalists to expand their activities using social media. It has brought journalists closer to their audience allowing a two-way conversation and a real connection. It is a great way of contacting people, to help the journalist see what’s trending and also to use as a publication method either in support of a more traditional publication or as a sole method. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and all the others each have their own pros and cons. This means today’s journalist relies heavily on social media to find out what is going on and to tell others about it. But, although the ethics have not really changed, the fast pace of social media and the direct contact with sources means journalists need to take extra care and be fully aware of potential pitfalls.

Social media as a source

Social media is a great source of news and features, both providing new and interesting contacts, showing trends of public interest and identifying possible stories. However, it also adds new concerns in order to adhere to standard practice as identified in the various codes in the UK such as the National Union of Journalists, the BBC, Ofcom, the Independent Press Standards Organisation and Impress. Anyone publishing on Twitter should understand it is a public forum and it is therefore perfectly acceptable to follow anyone who fits into your field of journalism whether they are celebrities, sports people, local councillors, trade unionists, campaigners, charity workers or just noisy know-it-alls. However, to ensure the story is suitably accurate, it needs to be confirmed elsewhere. This is usually easy to do with an authority source or even by sending out a general call for confirmation on social media.

Journalists also need to be careful about privacy. The recent scandal involving Cambridge Analytica and Facebook shows just how significant privacy can be. Mark Zuckerberg, CEO and co-founder of Facebook, told the Cruncie Awards in San Francisco in 2010: “People have really gotten comfortable not only sharing more information and different kinds, but more openly and with more people.” Following his 2018 appearances before a House of Representatives hearing in the US, Zuckerberg seems less confident about this.

Scraping data from Facebook pages is widely practised but its ethics are more complicated. People put information about themselves on Facebook and other social media, on the assumption that only those who know them can access it and that certainly only those who know them would want to access it. We can liken it to a group of friends gossiping around a table in a public place who do not expect eavesdroppers and certainly do not expect to see their views repeated later in a news story. Of course they are wrong. A person dying in bizarre circumstances on holiday or involved in a major disaster may suddenly become very newsworthy and accessing their Facebook page will bring pictures, data and potential contacts to further the story. Is it appropriate to access such intrusive pages despite high privacy settings or because the subject did not fully understand how to set high privacy settings?

The Independent Press Standards Organisation has dealt with a number of such complaints. The Herne Bay Gazette carried a story about a young woman jailed for causing death by dangerous driving and drink driving. They used a photograph from her Facebook page showing her holding up a full wine glass toasting a ‘booze-fuelled Christmas trip just days before she was jailed’. In fact the picture was taken on a family outing and the glass contained cola. She said that her Facebook page was set to family and friends but the newspaper said it was publicly accessible. The Ipso upheld the complaint (ipso.co.uk).

Twitter can also get you into problems. A woman complained to Ipso after a photo of her daughter was published on the front page of the Daily Star identifying her as one of the people missing or dead following the terror attack in Manchester Arena; the caption identified her as ‘missing’ and referred to her by a false name. Ipso upheld the complaint and required the publication of an adjudication after hearing that the complainant’s daughter’s details had been appropriated and used by a hoax Twitter account. The newspaper had taken no further steps to establish the accuracy of the claims on the Twitter account.

If journalists access social media for publication, they should confirm privacy settings and accuracy. Fully private settings should only be breached if there is a significant public interest.

Other issues to consider are:

- Is the subject a minor? If so the public interest needs to be overwhelming.

- Think about the nature of all the material. Just because a road accident concerning the subject is in the public interest, it does not mean that other details of the subject are appropriate to publish. Health (including injuries) requires a much higher level of public interest.

- Take a screenshot of the page with privacy settings to confirm what was there.

- Who placed the material on the page and is it therefore still appropriate to use it?

- When was the picture or item published by the user? Is it still current and appropriate to use?

- Is the material likely to intrude on anyone’s private life, grief or distress without an over-riding consideration of the public interest?

Ipso also offers guidance on social media use (https://www.ipso.co.uk/press-standards/guidance-for-journalists-and-editors/social-media-guidance/ accessed June 21, 2018).

Some stories on social media could be hoaxes. Much material comes from unofficial or commercial sources and needs to be treated with suspicion. The rise in conspiracy theories can probably be laid at the door of social media as anyone with a campaign, no matter how ridiculous, can not only find an audience of potentially millions but also sufficient people to take the idea seriously to give it some authority. Credibility and balance is difficult to measure on the internet without seeking additional sources. Try googling ‘Flat Earth Society’ (320m hits) to find just one group that is apparently growing its membership by 200 a year. There are plenty of other conspiracy theories or hoaxes that continue to circulate on social media, some of them decades old and even some that have been recently updated (see Frost 2000 and 2002).

Social media for publication

Social media is a useful publishing medium either to promote publication elsewhere or as the sole publication. However the limited nature of publication on sites such as Twitter can lead to problems, especially with automation starting to be more widely used to provide links and support.

In one recent case, a dodgy curry house in south London was prosecuted after a rat appeared during an environmental health inspection. The report put out by a magazine was safe but the website automatically generated a libel when a pop-up headed ‘Similar stories’ flagged up a meal review about another restaurant in the same area. The stories weren’t similar at all. The review was very complimentary, and the restaurant was in no way ‘similar’ to the one with the rat.

In another example a ‘similar stories’ tool picked up a link to a story that named a woman who had since been given anonymity as a rape victim.

Other problems specific to social media include ensuring stories can stand on their own. Reporting from court, for instance, can lead to contempt if care is not taken or if you forget to number link several tweets. Since one of the advantages of publishing on social is speed, it is also important to remember to correct any false information as soon as possible.

On professional social media

Wherever a journalist is working, it is important to remember personal views and those of any employer should never be confused. This may mean keeping personal views private – journalists do not always have the same option of parading personal views on social media that is open to many others for fear of damaging the accuracy and neutrality of their professional work.

For instance, the BBC says:

“…when someone clearly identifies their association with the BBC and/or discusses their work, they are expected to behave appropriately when on the Internet, and in ways that are consistent with the BBC’s editorial values and policies…

“Our audiences need to be confident that the outside activities of our presenters, programme-makers and other staff do not undermine the BBC’s impartiality or reputation and that editorial decisions are not perceived to be influenced by any commercial or personal interests.”

(http://www.bbc.co.uk/editorialguidelines/guidance/social-networking-personal/guidance-full accessed 8/5/18)

The BBC has plenty of other good advice about social media in particular about appearing impartial on websites. Whilst this is important to a public service broadcaster controlled by the Broadcasting Act it may not apply to newspapers or other websites that are happy to take a partial view. However, most publications do expect their staff to largely adhere to the ethos of the organisation.

Personal ethics

Journalists use social media both to gather information and to publish it in a way that means they need to be more careful about personal social media outings. Details of personal lives conflicting with professional lives have always been a problem with some journalists deciding they should have no personal life at all – not something many of us are prepared to stomach. For those of us who live in the real world where we can have beliefs and concerns it has always been wise to let your news editor know if your hobbies, beliefs or pastimes risk coming into conflict with your work. That has become even more important as more of our lives become public record on various social media. When we start Tweeting and social networking as a person, not a reporter we can easily run into problems with our readers or our employers.

Journalists around the world have faced reprimand or even dismissal for a thoughtless tweet or Facebook comment. Octavia Nasr lost her job as CNN’s senior editor for Middle Eastern affairs for a tweet that caused a furore among some Israeli supporters. Brian Pedersen was fired by the Arizona Daily Star for ‘inappropriate and unprofessional’ tweeting. Gavin Miller, the Australian radio announcer, was dismissed ‘a severe breach of the station’s social media policy’. The list goes on.

Copyright

It is important to remember material on the internet and social media is somebody’s copyright although it’s not always easy to work out whose. The pictures may well be the copyright of corporations, the subject’s family members, friends or even professional photographers. Whilst plenty of material is placed on the web and social media by organisations in the hope of attracting other publishers, journalists always need to ensure copyright permission has been granted before publishing. This also applies to stories in other publications. Plagiarism is difficult to prove, especially in the area of news, but lifting quotes and other details from stories published elsewhere, risks copyright infringement and also risks spreading inaccurate or false stories that have not been properly checked.

Archive

Another issue which has grown in significance over the past few years and will only become more important is archive material on the web, including social media. Stories on the web form a superb archive of material published by news providers. While it has always been possible to research newspaper archives, this is cumbersome and time consuming, and so such research is normally only carried out for very good reason. Now archive searches are quick and easy so any error in the archive, or any invasion of privacy will easily be discovered and publishers are having to reconsider their policies about archive material. For instance, imagine a person was arrested in connection with a series of serious crimes and a report appears in social media and on a website but a few weeks later the charges are withdrawn as the person arrested is found to have no involvement at all. Every time someone searches that person’s name, the arrests will come up. This makes it more important than ever to ensure the end story is published at the very least in a tag on the website. Newspapers and broadcasters are being increasingly bombarded with requests to ‘unpublish’, to remove references to people according to Kathy English, public editor of the Toronto Star. (2009: 6). This is not about errors, the main concern now is legitimate, accurate stories that may make life very difficult for a person in an age when searching is so easy. The GDPR and the UK’s Data Protection Act now lay down stringent guidance on the right to erase or amend data – the so-called right to be forgotten. Whilst publications’ archives are not normally affected, search engines can be.

Harm and offence

A previous Director of Public Prosecutions, Sir Keir Starmer, in guidelines on harm and offence, identified two broad categories: messages that contain credible threats that would be prosecuted robustly and messages that are offensive, insulting or controversial but should attract free speech protection. The main difference between harm and offence is harmful messages will contain credible threats whist offensive messages will not. While few journalists look to be offensive, it is a mark of free speech that messages which could be considered offensive attract the protection of free speech, otherwise what does free speech mean (Frost 2016: 197-209)?

The enduring importance of journalism ethics

Whilst web publishing and social media have been developing, the ethics of journalism have been developing as well. The rise of propaganda, rumour and fake news on social media means more than ever, if journalism is to be taken seriously – and it needs to be if we expect people to pay for it – it also needs to be ethical. News should be gathered from trusted sources or be supported by other trusted sources. Journalists need to be careful about gathering information unethically and ensure what they are publishing is the truth. Thirty years ago, journalism ethics were important but now they are vital. Media which seek to profit from informing the public, needs to ensure its public gets its money’s worth.

* Chris Frost is Emeritus Professor of Journalism at Liverpool John Moores University and has been a journalist, editor and journalism educator for more than 40 years. He is a former Chair of the Association for Journalism Education in UK , President of the National Union of Journalists and a former member of the UK Press Council. Copies of ‘Anti-Social Media’ are available to HoldtheFrontPage readers at a reduced rate of £15 by emailing [email protected] and quoting the name of this website.

Follow HTFP on Twitter

Follow HTFP on Twitter

“if journalism is to be taken seriously – and it needs to be if we expect people to pay for it – it also needs to be ethical”

”we expect people to pay for it”

”pay for it’

As long as the grossly subsidised Aunty Beeb reigns supreme on the www, then I can’t seen that happening………..

Report this comment