A group of distinguished journalists and academics, including two former regional press editors, have come together to take a look at how the phenomenon of social media has impacted on journalism, politics and wider society.

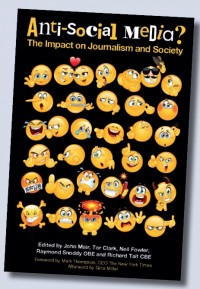

John Mair, Tor Clark, Neil Fowler, Raymond Snoddy and Richard Tait have co-edited a new book called ‘Anti-Social Media?’ which will be launched tomorrow afternoon at London’s Frontline Club.

We are serialising three chapters from the book on HoldtheFrontPage this week, beginning yesterday with industry veteran Alan Geere’s look at modern-day newsrooms.

Today, media analyst and former Scottish Newspaper Society director Jim Chisholm looks at the impact of the so-called ‘Big Five’ digital players – and argues that, not for the first time, rumours of the death of newspapers have been greatly exaggerated.

It’s 60 years since Francis Williams, forebodingly noted in 1957, the closure ‘of at least 225 weeklies and 21 out of 41 regional morning dailies’. Since then countless others from Bill Gates to The Economist have anticipated the newspaper’s extinction.

I’ve got some bad news for those harbingers of doom. To borrow The New York Times’ misquote (ha ha) of Mark Twain: ‘The reports of our death are greatly exaggerated’.

There is nothing we newspaper folks report more enthusiastically than our own demise! As I’ve written before, the news is flourishing but just not as we knew it.

Some harsh realities….

- In Europe the average print newspaper has about five years of viability;

- Bar some exceptions, digital revenues (and critically gross profit) are not growing as fast as print revenues are declining;

- The notion of paywalls paying – with some notable exceptions – is unlikely. News media have always depended on advertising, and here lies our core challenge/opportunity;

- The reason that news media – and other aspects of life – are under threat, is in large part because of the unfettered control and revenue extraction of the Big Five digital giants: Alphabet, Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Microsoft.

- The belief that young people simply do not connect with traditional news media. They turn to Facebook and Twitter for their news. That our youth somehow adopt news media as they get older couldn’t be more wrong as this chart of cohort behaviour over time shows:

History shows the media has a Darwinian way of turning adversity into advantage through adaptability. Records (vinyl) suffered from the launch of radio in the 1920s but musicians soon realised that radio was their best form of promotion. More recently musicians have turned the disruption of Spotify and YouTube to their advantage, bypassing the middlemen to attract new fans and buyers.

Digital audience broadcasting (DAB) has rejuvenated the radio industry, with a long way to go, for example linking location and personalisation tools to deliver new services during drive time.

Cinema was ravaged in the 1960s and 1970s by the arrival of television. Then first the DVD, and more recently the likes of Netflix, have not only rejuvenated film-making, but also cinema attendance. Now the BBC, ITV, and Channel 4 are having to gang up to take on the increasing threat of Netflix.

I first anticipated the rejuvenative opportunity of mobile in 2004, but it wasn’t until 2012 that mobile was measured as an advertising platform and then it was only in 2016 its audience was measured. Today, mobile accounts for two thirds of all digital and approaching a third of all advertising expenditure. And it accounts for around half of all newspaper readers. All this in 18 years.

Media evolve in waves with long periods of little evolution, interspersed with short periods – five to tens years – of frenetic disruption.

From the invention of paper in the seventh century, to Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press around 1439, to the world’s first newspaper in 1605 took around 700 years.

Some 170 years later, we had:

- Telephony in 1876;

- The phonograph in 1877;

- Photography in 1888;

- Radio around 1894;

- The first movies emerged in 1895.

TV broadcasting began in 1936. And while the computer’s first rudimentary form was an arithmetic machine by Blaise Pascal in 1642 and the first mechanical computer appeared in 1833, digital computing only emerged in 1936.

The revolution in personal computers and the internet occurred in the late 1990s. Around 20 years. Does it sound familiar?

Mobile followed a very similar trajectory. The internet’s evolution over 25 years, has now reached the inevitable point where a few major players – Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft (the Big Five) – completely dominate the digital world, and increasingly other aspects of society.

This domination must be questioned. And in some cases the question should be asked as to whether all or some of the Big Five should follow the 1984 breakup of the mighty Bell Corporation. However, the big question is why have other forms of media adapted and exploited technological disruption, but news media continues to struggle?

Strategic framework

There are two frameworks that will define the future viability of news media:

The first reflects media consumption in terms of:

- The forces of demand and supply; what do news consumers want/need and what are news providers offering;

- The roles of the established, legacy players versus emergent media;

- Demography, be it age, wealth, education or ethnicity. Binary political beliefs – right and left – are now a thing of the past.

The second is the definition of the digital news revenue value chain. Once it looked like this:

In this version of the digital value chain, generally 10 per cent to 15 per cent of the advertisers’ spending, is taken by the media-buying agency (plus creative costs).

Today it’s more like this:

The econometric impact of this on publishers is stark.

In this version of the value chain, for every £100 that an advertiser spends, only 29 per cent ends up in the hands of publisher.

However, a number of independent intermediaries that allow publishers and advertisers to bypass the dilutive effect of the Big Five’s value-chain grab, are reporting considerably higher returns while also removing the maelstrom of complications surrounding GDPR and how it is being interpreted/manipulated by the media agencies and Big Five.

Such an approach can more than double the share of ad spend that the publisher receives. But it will also increase the typical advertiser’s return on investment (ROI) by up to five-fold, because of more effective targeting, and end-to-end visibility, without wastage.

Publishers are scratching around looking for paywall models, simply because such a high proportion of advertiser spend is being lost to the Big Five. And historically and looking forward news media have relied on advertising to deliver the majority of their gross profit.

Looking forward, what will the news media landscape look like in, say, five years’ time? It was Donald Rumsfeld who infamously said: “There are known knowns, known unknowns, and unknown unknowns”. And it was 111 years previously that Oscar Wilde wrote: “The public have an insatiable curiosity to know everything……except what is worth knowing….. journalism…. supplies their demands.”

Today quality journalism is torn between society’s insatiable thirst for trivia, and President Trump’s and others’ attempts to present news as fake. The only consistency is tumultuous change, affecting every element of society, for better or worse.

After the boom years from 1950 to 1990 we must assume that economic growth rates will return to the historical norms of one per cent to 1.5 per cent. The erosion of fair wealth distribution means that today’s young people are the first generation to earn less than their parents and also the first to anticipate a shorter life expectancy. No wonder they ignore ‘reputable’ media in favour of social media.

We will continue to see the demise of the High Street (and now malls), with major retailers announcing closures or consolidation on an almost daily basis, as the Big Five grab this turf as well. In the last year (2017-18) 6,000 shops have closed.

Meanwhile, technology itself is evolving rapidly:

- The digital environment is increasingly dominated by mobiles and tablets. By 2020 more than a third of all advertising – and two-thirds of all digital – will be on mobile platforms.

- Mobile networks will continue to develop, with expanded bandwidth, and availability, and also advances in micro-payments, linked to the phone subscription, enabling more automated payments; think PayPal meets Vodafone.

- We read more and more about artificial intelligence, robots, data journalism, virtual reality, etc – but my view is that while these may enhance content provision, they are secondary to the need to identify viable business models given the disruption in the value chain.

In 2018, as I write, governments, at least in Western Europe, have recognised the importance but plight of the news industry. In the UK, the Prime Minister instigated the Cairncross Inquiry into the future of the press. In France and Germany there are already government initiatives to control the influence and impact of the Big Five. In Brussels the European Commission is proving forceful in cracking down on the Big Five’s excesses. But what we must not assume, in the UK at least is any helpful intervention from government, anytime soon.

The implications of this in terms of product development and most critically our crucial role as the fourth estate in society require significant consideration.

From lessons to directions

So, putting all this together, what are the lessons, directions and ideas that might reinvigorate the news industry?

At long last publishers are realising that they must escape their Stockholm Syndrome relationship with the Big Five, which has strangled revenues, stakeholder relationships and the reputation of news. There is an urgent need to redefine the respective roles of all stakeholders and intermediaries in the value chain to address the punitive effect that the Big Five and other intermediaries are having on content creation.

And I would include in this the increasingly redundant agencies and media buyers, as advertisers claw back control of the advertising value chain.

Unquestionably the likes of Alphabet, Amazon and Facebook can contribute greatly to the distribution of news, but not at the expense of revenue and stakeholders’ rights. In the future the Big Five should be our recruiters, not distributors. No more taking our content and audience control to their advantage, from now on they should simply divert visitors to get their content directly from the publishers’ sites.

The new news and what is happening

CP Scott, editor of The Guardian famously said: ‘Comment is free. Facts are sacred.’ So news media must reinforce its reputation. New approaches to news that appeal to the young and disillusioned are part of this evolution.

But to demonstrate how the news industry is thriving, let me first focus on my birthplace Edinburgh, a population of 500,000. It’s very sad that the area’s flagship newspaper, The Scotsman has seen its circulation fall over the last 40 years from 100,000 to 20,000, of which half are full price. Some of this is due to the growth of The (London) Times, which has seen circulation rise from 16,000 to 25,000 in the last five years, driven by investment in content. Established evening and local weekly papers have seen significant falls – but the consequence – not cause – of this is a raft of new initiatives:

First, community newspapers:

- South of Edinburgh, the Hawick News was a dominant local newspaper until its parent company made its senior editorial staff redundant. One of them launched the Hawick Paper in competition. After two years, the Hawick Paper outsells the News by more than two to one. Same people. Same market.

- In a tiny district of Edinburgh, the Broughton Spurtle, produced and distributed by a group of up to 70 volunteers enjoys a circulation of 2,500 and a monthly online base of 12,000-15,000, (in a community of less than 10,000) based in a local florists. Subscriptions are ‘£15 or whatever you can afford’.

- Across the city there are 44 defined communities, whose community councils each produce a newsletter of varying quality, mostly online, but in many areas a printed publication, funded by local advertising.

Then there are the more serious digital news media:

- Daily Business, founded by a previous business editor of The Scotsman, and now described by one of Scotland’s leading entrepreneurs as ‘My first go-to read of the day’, a sentiment echoed by many. It is funded by advertising, sponsorship, paid-for-content, a range of business-to-business services, and voluntary payments.

- The Ferret is an award-winning, not-for-profit consortium of experienced, independent investigative journalists. Their stories are regularly republished in the national and international press. It is funded through voluntary subscriptions, and contribution fees.

- Holyrood Magazine covers the activities of the Scottish Parliament every fortnight in print and digital formats. It is funded by subscriptions, advertising and sponsored content.

- Humans of Edinburgh is a Facebook site created by a young Edinburgh photographer that every day interviews someone on the streets of the city. It was the first medium to report that film producer Danny Boyle would be making a sequel to Trainspotting: The scoop attracted more than a million visitors and was picked up by dozens of news-media around the world.

Then there are innumerable niche publications covering entertainment, sport, lifestyle, and tourism, and the inevitable student newspapers, which are distributed free of charge across the city, each with accompanying websites.

Without access to detailed figures, it would be reasonable to assume that this myriad of ‘new news’ media collectively create a local media economy at least equal in size to the established media.

Alternative thinking on revenue

What is evident is the increasing reliance on voluntary subscriptions. The Guardian is the most significant example. It now boasts over 800,000 ‘supporters’ globally, of whom 500,000 make recurring monthly payments (as subscribers, members or recurring contributors), and 300,000 who are one-off donors. This may be a tiny fraction of the medium’s 150m visitors worldwide, but their impact on the publisher’s future viability has been dramatic.

This, combined with significant, largely operational cost savings, has resulted in The Guardian halving its losses to £18.6m on a turnover up one per cent to £217m, at a time when most publishers are reporting revenue declines.

Today in 2018 more than 50 per cent of turnover comes from digital, up 15 per cent year on year; reader revenues from donations and print circulation now outweigh advertising sales. The group is on course to break even on an operating basis in the new financial year,’ it says.

Who are the new newsers?

One observation I would make is that, with notable exceptions, most of these new news media are produced by talented, seasoned journalists, who have become either disillusioned or deemed dispensable by the corporate publishers. Here is firm evidence that the decline of the traditional press is not a fault of its ever-declining number of employees. Many of the new news success stories across the UK have been created by staff well into their 50s, and beyond.

However, with the exception of the thriving student press, very few new products are being produced by the under 35s. In addition, very few women appear among these new news players.

If established publishers want to survive, they must seriously focus on the needs of millennials, whose needs, interests and views are never going to be satisfied by their current offerings.

Where’s the money?

Not surprisingly, most new initiatives are led by journalists. With no disrespect to these often brilliant, pioneering writers, I observe a lack of commercial expertise and in many conversations, I would suggest there is also commercial naivety. There has always been a healthy conflict between the content creators and the moneymakers, but today realism must prevail. At one time newspaper organisations employed as many commercial staff as editorial. Now the ratio is around two journalists to every one revenue generator. In the new news world the emphasis is strongly on content with often little regard to the realism of revenue.

This problem is exacerbated by the fact that these are small operations fighting for funds from fewer, ever-larger, media-buying houses. This need is reflected in the many attempts by the national press to work together in their selling activities, the latest being the joint-venture between The Guardian, Telegraph and News UK.

The same is true of technical systems, where smaller publishers are at a disadvantage in terms of acquiring top-drawer scalable content management and commercial software. Referring to Berkshire Hathaway’s decision in the USA to outsource the management of its small network of newspapers, Rick Edmunds of the Poynter Institute noted: “It’s harder for smaller companies to keep up with technology needs and centralize operations like larger media companies have.”

However, time has shown even the biggest publishers are struggling to make headway against the dominance of the Big Five. To this end I have long advocated the creation of an Association of Independent Publishers, that provides a platform for mutual support, idea exchanges, cross-market networks, but as importantly, a collective approach to commerce, technology, training, legal services, etc.

And in the end…

For many printed newspapers extinction awaits. The question is how many of them will survive the point of inflection from print to digital profitability. Some undoubtedly will. But others will succumb to the Big Five and their own mismanagement.

The good news is the flourishing new news. But to succeed, these excellent publishers need to adopt the entrepreneurial skills as they demonstrate in editorial. The new news has a bright future in tomorrow’s society, but unless the Big Five are reined in, who knows what will happen?

* Jim Chisholm is an international media consultant and analyst. http://www.jimchisholm.net/mediatrix/about-chisholm/ . Copies of ‘Anti-Social Media’ are available to HoldtheFrontPage readers at a reduced rate of £15 by emailing [email protected] and quoting the name of this website.

Follow HTFP on Twitter

Follow HTFP on Twitter

“….At one time newspaper organisations employed as many commercial staff as editorial. Now the ratio is around two journalists to every one revenue generator”

Where in the uk regional press is this the case? Certainly not at all the bigger regional publishing groups I know of where editorial departments have been cut to the bone while the sales floors are still full to overflowing with ad reps, telesales and as many managers as ever.

and on that matter,who calls ad reps ‘revenue generators’?

As the author is described as “ an international media consultant” I assume most of his analysis and findings are from a global perspective( look st the terminology used) rather than being a true picture of the state of the uk regional press.

Report this comment

HTFP is a site covering news and comment from the country’s local regional papers yet this piece includes global trends and a par on media-buying houses when majority of local papers, from the big groups to the small independents,still use local sales reps rather than MBA to generate commercial revenue from hyper local community businesses.

The piece about new independent papers appearing is relevant but it’s hard to take much of this analysis seriously when it relates to global rather than the uk regional press,analytical charts from eight years ago, when so much has changed in the past three to four years alone, and with an over abundance of American examples and terminology.

Report this comment

Hi prospectus,

Thanks for your comments:

Trinity Mirror (now Reach) 2017 annual report (p 12)

Editorial: 2,121

Advertising: 1,183

JP’s 2017 Annual Report (p 95) does not provide advertising specific stats, but I would “guestimate” that there are roughly 31% more editorial staff than advertising sales. In the last year reported, editorial staff reductions were 5.1%, while those in “sales and distribution” fell by 21.7%

Yes. My statement also includes figures from the USA, and anecdotal figures from European publishers.

I have sympathy with your comment: “editorial departments have been cut to the bone while the sales floors are still full to overflowing with ad reps, telesales and as many managers as ever.” But I can assure you that – excluding digital – ad staff feel equally targeted.

Your point re numbers of managers reflects well the comments at: https://www.glassdoor.co.uk/Reviews/Johnston-Press-Reviews-E10296.htm

The “New Newsers” are a great demonstration that putting love, sweat and passion can deliver great results for News and for our increasingly broken society. But this needs equal re-engineering of the revenue generating machine.

If we can resolve the shit caused by the Big Five (and now Amazon), then there can be plenty of revenue to rebuild editorial brilliance and BTW, even we stats clerks are in this for the passion).

But until governments sort the gross domination of the Big Five/Six, to allow publishers and advertisers to re-engineer the digital value chain, the rest is shifting deckchairs.

More than happy to have a private debate on email: [email protected]

Report this comment

they got the title right at least. Anti-social it most certainly is.

With newspaper sales down as much as 90 per cent from peak for many papers I admire their optimism but feel a little more research into sales might have revealed a darker forecast in the UK.

Report this comment

I don’t think Mr Chisholm has grasped the reality of the situation in the uk regional press in 2018 if he believes; “ ….In the new news world the emphasis is strongly on content with often little regard to the realism of revenue”

Content, or specifically ‘quality local news content’ takes a back seat in favour of ‘revenue generators ’ chasing any revenue it can get hold of, sorry but it’s ALL about revenue, in this country at least.

Sorry but there are too many American references and examples ,misconceptions about the uk industry and unrecognisable jargon for me to take this seriously.

Report this comment