The Westmorland Gazette is celebrating its 200th birthday this year with a series of events and exhibitions across its Lake District patch.

Here, freelance journalist and journalism lecturer Jeremy Craddock, who began his career there, describes how three eccentric and idiosyncratic literary giants helped shape the newspaper.

Poet William Wordsworth never intended to be a newspaperman but in 1818 he was talked into it by influential political figures in his beloved Lake District.

Although he agreed to help set up the Westmorland Gazette, he drew the line at becoming its first editor.

The Westmorland Gazette weekly newspaper in the Lake District will be 200 years old on May 23 and its unique history and pedigree is being celebrated in a new exhibition, as reported on HoldtheFrontPage.

The anniversary is remarkable not just because the title is one of the UK’s oldest newspapers still in existence but also because print newspapers are in decline.

But what truly sets the Westmorland Gazette apart is its unique history and pedigree.

Consider this: besides Wordsworth and Thomas De Quincey, a certain fellwalking author called Alfred Wainwright also had a hand in making the paper what it is.

Yet it all began so inauspiciously. Described in 2004 by the Guardian as ‘one of the world’s great newspapers’ it’s worth noting that the Westmorland Gazette was actually the second-fiddle paper in the town of Kendal in 1818.

It was only set up thanks to a political dust-up between the Whigs and Tories ahead of the 1818 election to contest the seat of Westmorland.

Whig Henry Brougham planned to fight Tory Lord Lowther at the ballot boxes and had the backing of the area’s Kendal Chronicle and Westmorland Advertiser.

This is where Wordsworth enters the story. Lowther sent Wordsworth to persuade the Advertiser’s editor to give equal coverage to the Tory cause. When Wordsworth’s efforts failed, the wealthy Lowther family bankrolled a new, Tory-supporting newspaper, The Westmorland Gazette and Kendal Advertiser.

It is thought the Lowthers wanted Wordsworth to be the editor, but he passed over the job and recommended a chap that posterity recalls only as Fisher. And so, on Saturday, May 23, 1818, the first edition appeared. Editor Fisher couldn’t stick it and shortly afterwards vacated the editor’s chair.

On Wordsworth’s recommendation, De Quincey replaced Fisher in July 1818.

It wasn’t the smartest of appointments, with hindsight.

De Quincey was a dedicated opium consumer, who went on to write The Confessions of An English Opium-Eater two years after his stint at the Gazette. As well as ripping off stories from other papers, he refused to leave Grasmere to go to the Gazette office in Kendal, preferring to stay at home and write about the hallucinogenic effects of being dosed up on laudanum. (In his last years, De Quincey was spending £150 of his £250 annual income on the drug, according to his biographer Frances Wilson.)

Quite what the readers of the Gazette made of this, it’s hard to say. While editing the Westmorland Gazette wasn’t to be De Quincey’s finest moment, nevertheless he left his mark on the paper and went on to greater things. He certainly left a mark on the great Argentine magic realist Jorge Luis Borges, who said: “I wonder if I would have existed without De Quincey.”

Could the proprietors of the Westmorland Gazette say the same?

A century later another literary figure would play a central role in the fortunes of the Westmorland Gazette.

Alfred Wainwright was a Lancastrian by birth, hailing from Blackburn. He had a love of drawing and, in particular, cartography, spending much of his childhood poring over maps and designing his own, meticulous efforts.

He first visited the Lake District in 1930 at the age of 23, and was stunned by the view of Windermere. A love affair with Lakeland and its fells began, one which would last the rest of his life.

Young Alfred – or AW as he would be affectionately known by family and friends – resolved to come and live in the Lakes.

It would be another eleven years before he moved to Westmorland to work at the borough treasurer’s office in Kendal (he would eventually become borough treasurer in 1948 until his retirement in 1967).

Recently it was suggested Wainwright might have been on the autism spectrum. This would explain his single-mindedness, meticulousness and devotion to order, as well as his awkwardness in social situations.

His biographer Hunter Davies has suggested his obsession with fell-walking and his guide books contributed to the breakdown of his first marriage to Ruth (with whom he had a son, Peter).

Wainwright began his brilliant, idiosyncratic series of Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells in late 1952, initially privately. The Westmorland Gazette was the original printer, but eventually became the publisher in 1963, from Book Six onwards.

TV stardom beckoned for the modest Wainwright when he made a series of programmes with broadcaster Eric Robson. He was interviewed on the BBC’s Desert Island Discs by Sue Lawley, but famously refused to travel to London, insisting Lawley come to Manchester. This was so that he could get back to Kendal in time to watch Coronation Street. He also insisted on having fish and chips at Harry Ramsden’s as part of the trip.

Wainwright’s success built slowly over time, his popularity among Lake District fellwalkers keeping him a cult for many years. But by the late 1970s the Westmorland Gazette realised it had produced almost a million copies of his beautiful books.

To mark the occasion, the general manager of the newspaper came up with a promotional stunt. A special mark was put in the millionth copy and it was announced that whoever bought it would win a package of prizes, chief among these being a meal with Wainwright himself.

What they hadn’t banked on was the reticent author’s reaction to such an offering.

Recoiling from the thought of having to make small talk over food sent Wainwright into a spin, according to his biographer Hunter Davies. The Gazette had kept tabs on the book and Wainwright and a Gazette printer went to Manchester to retrieve the copy from a bookshop.

The book was sent out again, but only after the prize had been re-advertised, this time without the promise of dining with the famous author. Hunter Davies notes that the copy went to a bookshop in Keswick but it has never been found.

The books made a lot of money for AW, but he never spent it on himself, eschewing a lavish lifestyle for a happy, quiet existence out of the spotlight with his second wife Betty. He spent his considerable royalties on setting up an animal sanctuary called Kapellan on the outskirts of Kendal. He always said he preferred animals to humans, anyway.

Wainwright died in 1991 and is now commemorated by Wainwright’s Yard, the shopping development and new Westmorland Gazette offices on the site of the original Gazette premises.

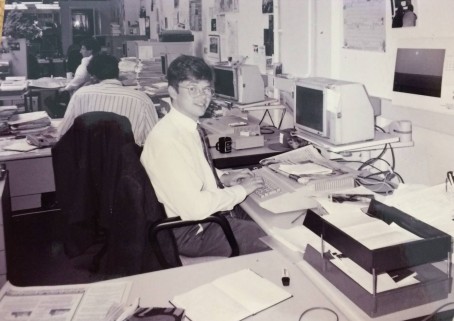

It was in the original building in around 1993 that I came across a hunk of metal lying forlornly in the dust of the old printing press room. I was a trainee reporter on the paper, six months into my employment. I was on my way to the archives room where a copy of every edition of the Gazette to that point was stacked untidily in tattered bound volumes. I picked up the metal hunk and realised it was a printing block for a page from one of Wainwright’s guidebooks. It was a beautiful reverse-image rendering of a Wainwright sketch and his immaculate handwriting.

After a few moments of rapture, I laid the block back on the dirty floor and went to scour the files.

The next time I passed through, the block had gone. I suspect it had been disposed of – Wainwright wasn’t quite the national treasure then that he has become. I kick myself that I didn’t keep it for posterity. Heaven knows what it would be worth now.

Follow HTFP on Twitter

Follow HTFP on Twitter